The monsoon was playing hide-and-seek with my small town for the last many weeks. All around the district, it’s been raining, nay pouring, like water’s going out of fashion. Heavily laden, low, dark clouds would come striding across my small town’s morning skies and housewives would wonder whether to run the washing machine that day, mothers would remind kids to put the raincoats back in school-bags, and office-goers would slip their collapsible brollies in the bag along with the lunchboxes. But the clouds would hang around like a bunch of no-gooders, and disappear into the night, only to reappear the next day bursting with the promise of rain but only blessing an area here or there with a quick light drizzle. Nothing more.

Then, responding to the curses yelled at the disappearing clouds by a sweltering public, last Wednesday, the clouds decided to stay put and opened up. The steady rain lashed the town through the day, the water making its way, first down the gutters, and as the gutters filled up slowly, not keeping up with the speed of the pouring rain, the water gathered on the pavements, along the roads, snaking its way around the trees and the plants, creeping into the parked cars, whipping the sleepy crocodiles out of the sewage-filled lethargic waters of the Vishwamitri and onto the town’s streets. Ah the Vishwamitri! Which suddenly decided that it could become a river. Whoa! It once was a river! In fact, every year for a few days, it often became one, how could it forget? It is the one time that Barodians flood Instagram with Vishwamitri photographs -- a wildly flowing sheath of brown water, its waves savagely climbing up both banks, the strong currents forming dangerous-looking whirlpools, pulling along large branches of trees and tall bushes uprooted from the sodden banks.

The Vishwamitri river in quieter times … which is about 360 days in a year.

We are in the month of Ashaad, when the monsoon has fully set in across the country. The over 700-year-old Ashaadi Varkari’s annual pilgrimage on foot to the Vithoba temple at Pandharpur culminated on the Ashaadi Devshayani Ekadashi on July 17. It marked the beginning of Chaturmas this year – the four months of Shravana, Bhadrapada, Ashwin and Kartik – which will end on the Devuthani Ekadashi that falls later on November 12. It is believed that during these four months, Lord Vishnu is in Yog Nidra and it is an inauspicious time to conduct any celebratory events. Yet so many of the most important Hindu festivals fall in these ‘inauspicious’ months and I find that most surprising. I watch the Marathi channels on TV and this year, for the first time, I find many Ashaadi advertisements. What are these, you may well ask. They are for readymade masalas to spice the mutton, chicken, fish and egg dishes that are very popular during this month (mutton-wade in my community is a favourite!) as most people will forego non-vegetarian foods during the coming month of Shravana!

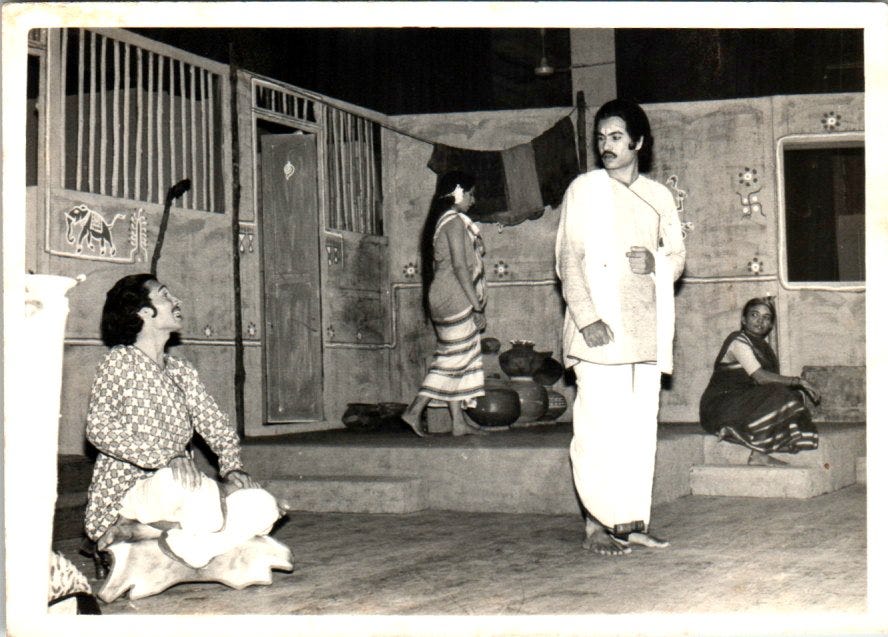

Mohan Rakesh’s play, Ashaad ka ek din was staged by the Dept. of Drama, Faculty of Performing Arts in 1981-82, directed by Prof. Yeshwant Kelkar. Above photo shows, from left to right, Akhilesh Nanavati as Vilom, Deepa Diwan as Mallika, Shirish Mohan Rao as Kalidasa and Namrata Vyas as Mallika’s mother. Pic courtesy Akhilesh Nanavati and Namrata Vyas.

Many decades back, I saw Mohan Rakesh’s path-breaking, powerful play, Ashaad ka ek din, presented by the Dept. of Dramatics, Faculty of Performing Arts, MSU. The 3-act play, directed by Prof. Yeshwant Kelkar, tells the fictionalised story of the young poet Kalidasa (act 1), living in the serendipitous forests of the Himalayan foothills, in love with the beautiful Mallika, already composing poems and being aware of his own genius. But the snake of ambition is slowly curling around his neck, drawing him away from his Garden of Eden to the rich and vast city of Ujjaini. There, his genius is recognized at the Court (act 2), his plays and poems applauded widely. He marries into nobility and lives a life that accords him undreamt of wealth and social prestige. One day he decides to visit his village accompanied by his wife and a retinue of servants. While he avoids Malika, his wife makes it a point to meet her and make her an offer of marriage and settling in Ujjaini, which she rejects. After several years, (act 3), Kalidasa, tired of the artifice of court life that has also dried up his creative juices, gives it all up and returns to rejuvenate himself in his village, alone. This time he goes to meet a heartbroken Mallika, who has in the meanwhile married Vilom, and has an infant daughter. Shocked, he stumbles out of her home. And the play ends.

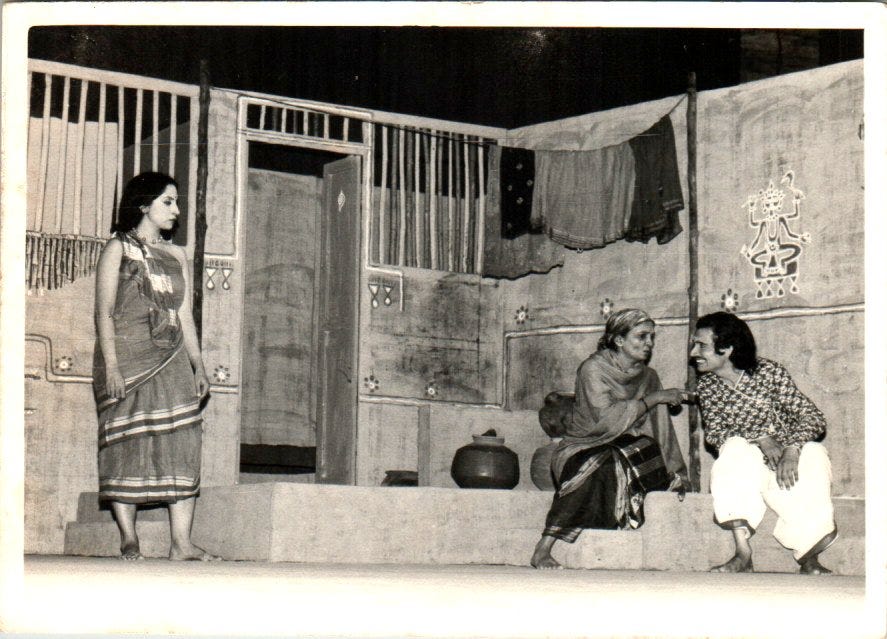

Mallika (Deepa Diwan), Mallika’s mother (Namrata Vyas) and Vilom (Akhilesh Nanavati) in Ashaad ka ek din. Pic courtesy Akhilesh Nanavati and Namrata Vyas.

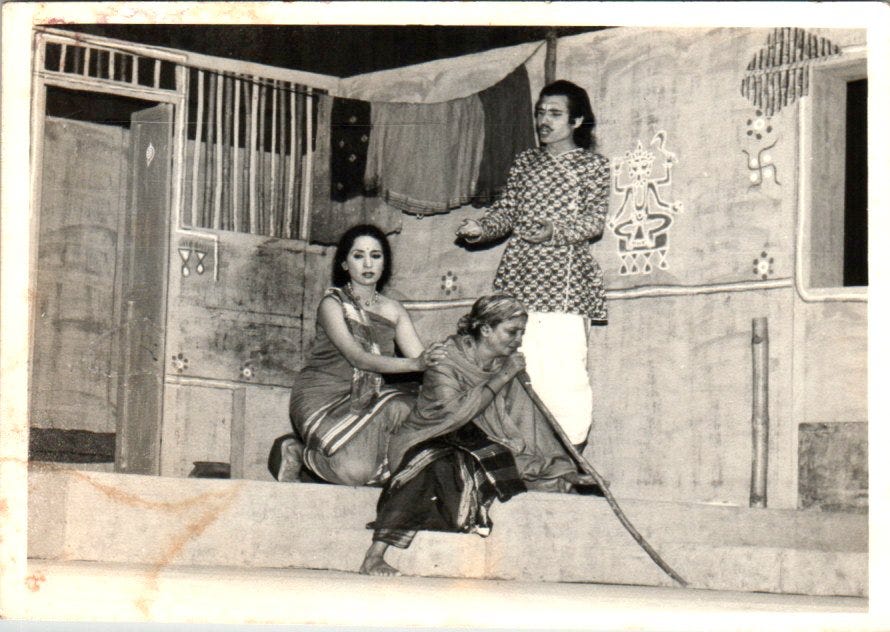

The complex play leaves you disturbed on many levels. It is no wonder that it has been presented by most of the top theatre directors of India, translated in many languages. In 1971, Mani Kaul made it into an award-winning film that continues to attract both bouquets and brickbats! The challenging play, which takes its name from a line in Kalidasa’s Meghdutam, is a fictionalized version of Mahakavi Kalidasa’s life whose centre is emotionally dominated by Mallika, his childhood sweetheart, not Kalidasa. The play explores the rather self-centred attitude of creative persons who do not really care for the people/environment around them on which they feed for their creative energy and ideas. Those who love them tolerate their eccentricities in the belief that they are being helpful and supportive but there really is no reciprocation when push comes to shove, and when they are the ones in need of the creative person’s attention. Mallika’s vulnerable condition only serves as a shock to Kalidasa, with no realization that he is directly responsible for it. In fact, it is quite possible that he is angered that she has let him down as she is no longer the beautiful, innocent girl who inspired the several heroines in his epic poems! While situating the plot of the play in historical times, Mohan Rakesh brilliantly puts forth the harrowing conflict faced by the modern human -- of choosing between ambition and love, between values and the craving for material wealth. When Kalidas and Vilom confront each other in the last act, Vilom asks, What is Vilom? An unsuccessful Kalidas. And Kalidas is a successful Vilom. Touche!

Vilom convincing Mallika that she should marry him and he will take care of both her and her mother! Pic courtesy Akhilesh Nanavati and Namrata Vyas.

And then on another evening of a cloudy-rainy Ashaad, I saw another exciting, provocative play, Lady Anandi: Redux, created by Anuja Ghosalkar who is its writer, director, actor, and brought to town by the Ark Foundation. Ghosalkar does ‘documentary’ theatre, which uses lots of archival material, such as photographs, handwritten letters, newspaper reports and so on, that creates and drives the narrative, such as is possible. It largely moves away from conventional dramatic theatre as we know it, so it ‘jump-cuts’ from a scrap of material here that connects to a bit of information there, to a historical or literary reference someplace else. At the end of the performance it might all come together or it may not – leaving the audience to regurgitate what they saw, heard and experienced – and draw conclusions of their own.

Anuja Ghosalkar in Lady Anandi: Redux.

Ghosalkar, facing issues with taking forward her theatre career down the mainstream mode, was searching for ways to make an inroad in her special manner. Fortunately, looking back into her own personal history, she found that her great grandfather from her mother’s side, Madhavrao Tipnis, was kind of pushed onto the stage to play feminine roles in the Gadhya Natak (as opposed to the Sangeet Natak) which was a popular form of public entertainment in the late 19th century, especially in Gujarati and Marathi. It was quite normal for young boys to play female characters and later graduate to male roles as they grew older. When she dug deeper, she found several photographs with detailed captions that indicated the roles he played, as a woman as well as a man. So collecting all of this priceless archival material, she took off on a month-long Residency and wrote this one-person play in which she uses props, video clips from past performances (this came post-COVID), audience participation, improvisation and subject matter that ranges from a line of dialogue from one her great grandfather’s ‘characters’ on stage to references from classical plays and historical events. And, of course, to gender bending. And loads of fiction too.

Lady Anandi, indeed!

Thank you, Miraji. I am glad you enjoyed it ...

Thank you, Hemant.