Many moons ago, when I was much more involved with the Bhasha Research and Publication Centre in my small town, and with its satellite, the Adivasi Academy at Tejgadh village in Chota Udepur district, I was contacted by eco-journalist Aparna Pallavi researching an interesting subject – local recipes made from the Mahuwa flowers of the majestic Mahudo tree that grew luxuriantly across the tribal belt of India, as well as in some parts of south and north India. She had already collected a number of recipes from several tribal and mainstream communities, and was looking to find more from the Rathwa tribals who were amongst the largest ethnic group of central Gujarat and western Madhya Pradesh and with whom the Adivasi Academy worked closely. We organized a one-day interaction between Aparna Pallavi and several Rathwa men and women expert in cooking (and preparing medicinal concoctions) with Mahuwa flowers identified by our team at the Academy. Both exchanged recipes, and these were not just limited to Mahuwa flowers but other unusual forest produce foraged by tribal communities as well.

A Young Mahudo tree near the Adivasi Academy, Tejgadh. Photo courtesy, Adivasi Academy.

In fact, this led to Bhasha working on a project where we collected a number of traditional recipes, those made especially during weddings, festivals, birth of a child as well as for rituals related to death and ancestor worship. These recipes are often remembered now only by elders in the community, as younger, urbanized tribals often opt for chole and paneer just like mainstream Indians cannot do without pasta and falafel counters at their festivities. The compilation of these recipes is lying dormant amongst the files at our Bhasha office and I need to fish this out and somehow make sure it sees the light of day as a published document.

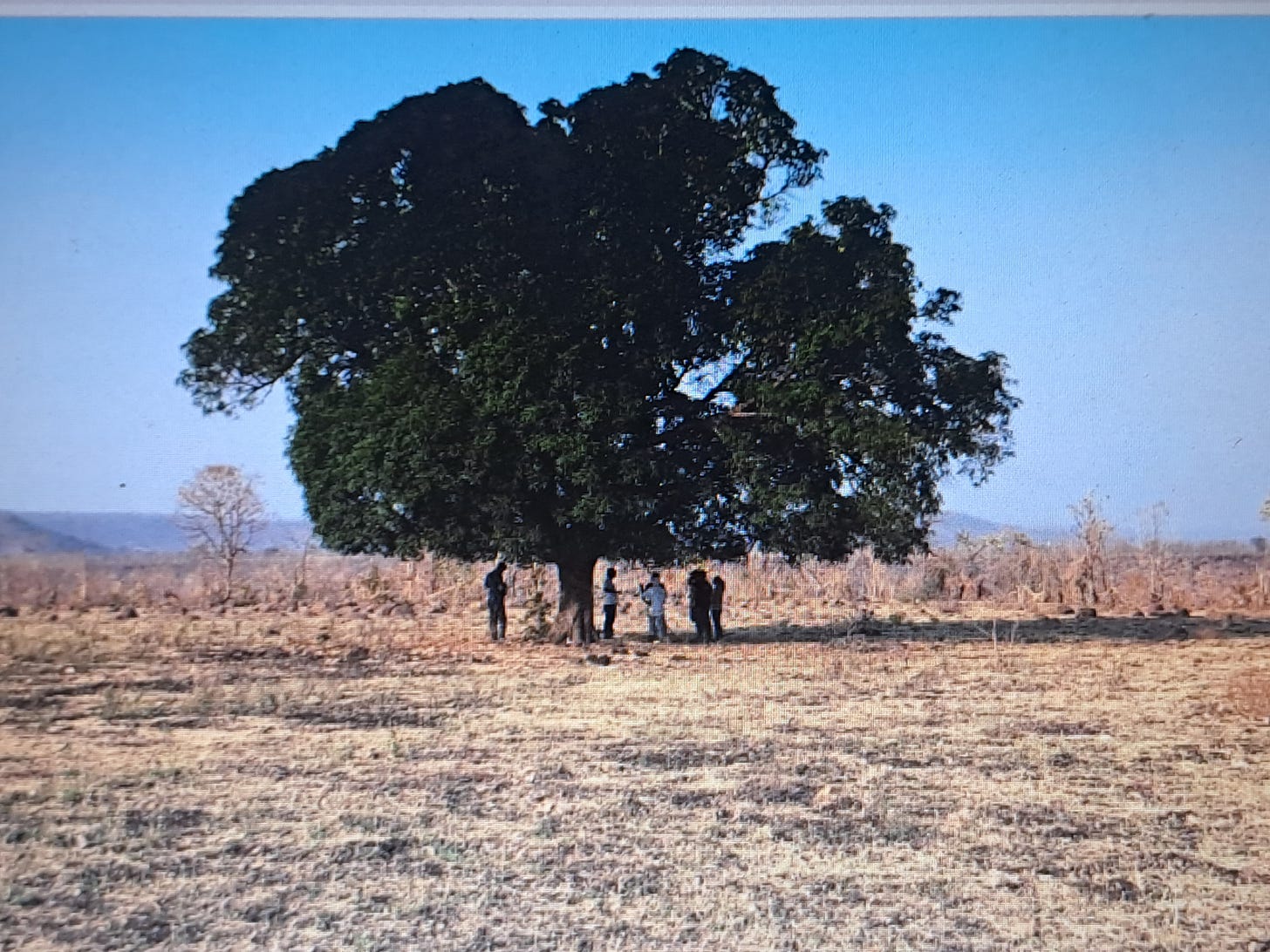

The old Mahudo just outside the Adivasi Academy. It grew from an outcrop of smooth rock. When the land was allocated by the Govt. of Gujarat for the Adivasi Academy, the first meetings, classes, administration was run from under the abundant shade of this now dying Mahudo. Mahudo trees usually live for 60-70 years. Even now, when any of us visits the Academy, we always bow to this wonderful tree before entering the gates of the Academy. Photo Courtesy, the Adivasi Academy.

In the meanwhile, the Mahuwa flower has blossomed again. And what a blossom! This time, in the form of the evocatively titled, Mah, the Spirit of the Forest, a premium, branded and bottled liquor-drink, quality-checked and promoted by a French firm, mahspirit.com, but currently only available in France at the rate of 40 euros for a 50 cl bottle! I had my first taste of the Mahudo (as the drink is called by the Rathwas who distill it) as a sacred offering to Babo Pithoro, the deity they draw on their walls and worship. We were at the ancestral home of Naginbhai Rathwa at Tejgadh village, one of the first persons to join us at the Adivasi Academy. His home housed an old Pithoro, painted in fulfilment of a vow made when his mother fell seriously ill many years back and her survival was a question mark. She soon recovered and has been fine ever since. A proud mother, she rose to greet and welcome us in her home, while Naginbhai passed around thick glass tumblers half-filled with a cloudy liquid – a far cry from the elegance of a French table d’hote – but very much attached to the soil. Potent and sharp, as it burned down our throats!

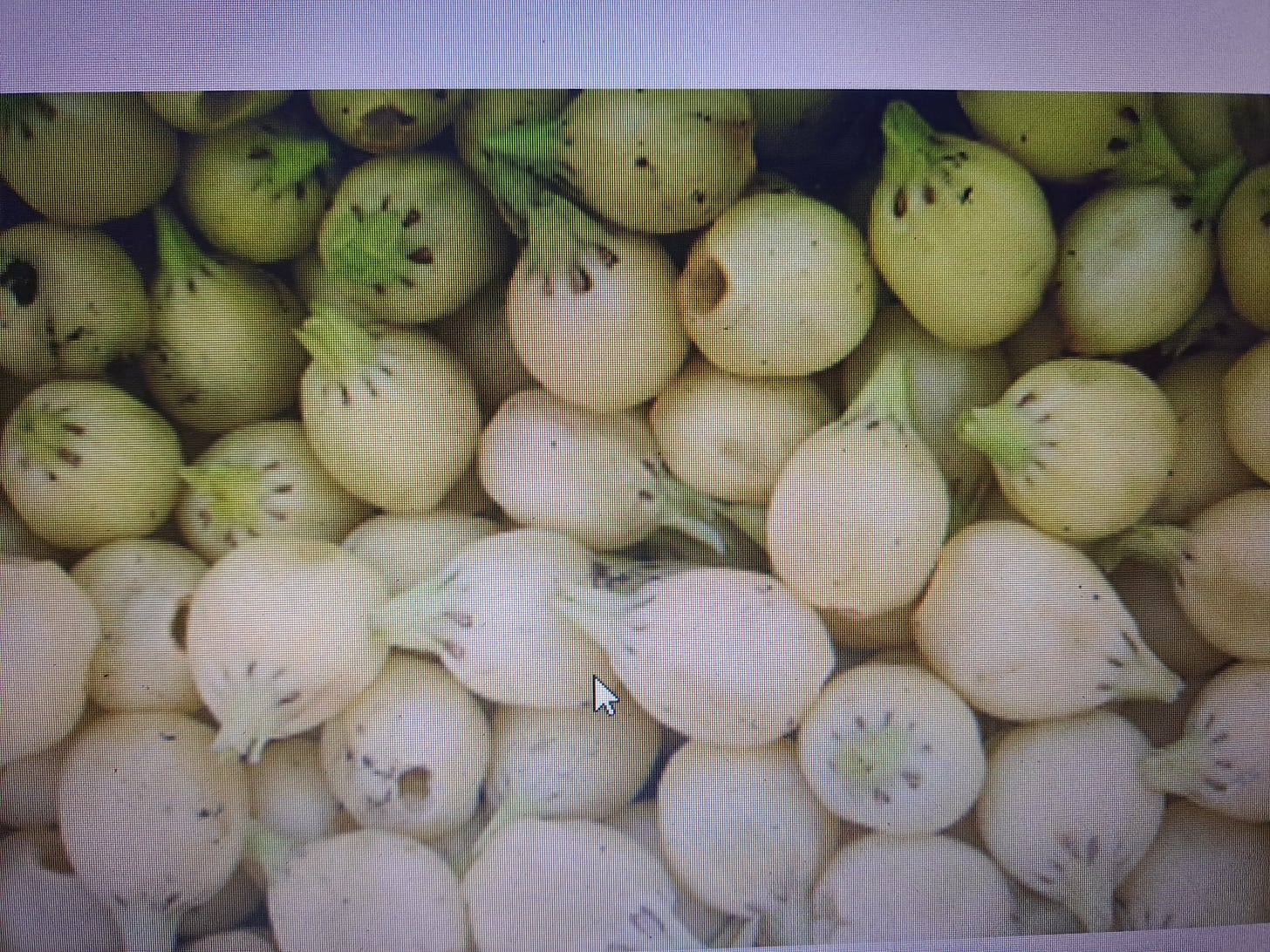

The Mahuwa flowers. Image courtesy Mah website.

The Mahuwa or the Mahudo tree is of very ancient origin and believed to be one of the few trees documented in ancient Sanskrit literature (‘mahuwa’ could be derived from ‘madhu’ or honey). Its bulb-like soft greenish-yellow flowers are sweet and juicy and produce an intoxicating drink ‘so delicious that spirits, animals, birds and humans alike are said to love it with equal relish’! The indigenous tribes of India look upon the tree/trees in their village as a sign of prosperity, a symbol of hope and good fortune, of nature’s largesse ensuring the village’s well-being. However, unlike several other natural produce collected by forest-residing communities such as bamboo, mushrooms, tendu leaves, honey, certain grasses, wild fruits and vegetables, the Mahuwa fruits are ‘burdened with a colonial legacy that has a conflicted history’.

Colonial authorities were interested in restricting local consumption of such spirits to make sure that revenue would be generated by its industrial-level production instead. In this project, they were supported by the anti-alcohol attitudes of the dominant Indian communities. This was perhaps true of other indigenous brewed liquors as well such as the Goan arrack and feni (made from fruits of the cashew, coconut and jackfruit) which still cannot be sold outside of Goa, South Indian toddy (made from sap of various palm trees), while different kinds of beers made from fermented rice/millets/barley were popular in almost all hilly, cultivated farmlands across the sub-Himalayan terai and well into the North-east.

Gathering the fallen Mahuwa flowers early in the spring mornings! Photo courtesy Mah website.

Fortunately, though, the colonial dream of turning these home-distilled and fermented spirits into mass-produced, conveyor belt pushed bottles, never saw light of day (I guess they found much more profit in selling India-grown and harvested opium to China). But, they did manage to ‘control’ Mahuwa ‘use’ as these trees were profusely spread across the breadth of central India, from Gujarat in the west to Bengal in the east, which is also the most important tribal belt, with a dense population of several communities. This ‘control’ came in the form of chopping down of these trees and discouraging planting of new saplings. Unfortunately, this attitude was continued in post-Independence India and even now, it is difficult to get Mahuwa saplings easily.

A flourishing, mature Mahudo tree. Such a sight for sore eyes ! Photo courtesy Mah website.

In many states, there still continues to be a ban on the sale of Mahuwa flowers in the open market, which was an important source of income for the local tribal community. Most of them would wake up at dawn and sit near the Mahuwa trees in their village or nearby forest to pick up the falling fresh flowers in the early summer months of March and April, before the birds and wild animals come around to feast on them. Collected in large baskets, some of the sweet and juicy flowers are dried in the hot summer sun, stored in air-tight bags, and fermented and distilled as and when needed for their own home quota of Mahudo; the rest are sold in the village haat. The fermentation process takes 3-4 days with about 15 kg of flowers distilling into 12 litres or so of liquor. Sometimes they also sell the liquor itself if they need the money!

So, now enters Mah in these Indian tribal hinterlands looking for the Mahuwa flowers and the locals who can relate tales about this drink of the Gods. Mah is an Indo-French collaboration, registered in France. It is a partner with Bastar Botanics Private Limited in India, through a joint venture – Bastar Spirits, seeking to develop a strong organizational base for the development of a local economy around Mahuwa. This includes making Mahuwa, archiving techniques of making Mahuwa in the region and developing a system of business practices for members of the local indigenous communities. As their CSR, since the past few years, they have offered Fellowships to handpicked locals from different tribal areas to document and collect material related to the Mahuwa.

The first two Fellowships went to Rajshri Bais, a talented woman from the Mahara community, Andhra Pradesh, based in Bastar, Chhattisgarh, and to Sachin Rathod, a young Mahuwa enthusiast from the Banjara tribe of Maharashtra, who followed the story of one particular tree, located in Vadoli village, not too far from his home in Maharashtra. That year it shed around 90 kilo of Mahuwa flowers in March and April, producing around 90 litres of Mahuwa spirit providing a supplementary income to the Shedmakke family who were its prime collectors and spirit makers. They collected the flowers between 5 and 9 am every day, sun-dried the flowers, fermented, distilled and sold the spirit by the glass in local weekly markets. Sachin’s research followed the trail of similar Mahuwa makers and examined steps required to increase the income of such families through Mahuwa and other forest produce. The next was Pappu Dulasing Jadhav, another Banjara from Kinwat Taluka, Maharashtra, who was mentored by Dudhram Bhoju Rathod. Dudhram explores livelihood opportunities for tribals from forest produce and also has experience in working with government administrative services. Pappu and Dudhram returned with new learnings about the Mahuwa tree and the community.

This year the year-long Fellowships have gone to Bhavsinghbhai Rathwa and Praveenbhai Rathwa from the Adivasi Academy, Tejgadh. Bhavsinghbhai is a trained sound recordist with an ability to understand documentation. He is moving from village to village with Mahuwa trees in the Chota Udepur district, documenting folklore and practises related to Mahuwa including songs, stories, myths, beliefs, ritual practices and food recipes. On the other hand, Praveenbhai has natural skills with textile dyeing. He is experimenting with the use of Mahuwa flowers for the fermentation process in the production of organic indigo that is grown near the Academy and used in the loin (Kasota) loom weaving being revived at the Academy. An English language professor of a college in Chota Udepur has offered to translate their documentation and findings in English.

Mah believes that it is possible to collaborate across the globe and strengthen local initiatives at the same time. Mah is therefore an attempt to make visible a drink that belongs to the communities connected to India’s forests, and making it with the experience of the skills and proficiency of the Cognac region is the French side of this collaboration. It is an important part of the process to make it known around the world. Mah hopes to unfold a process in which the forests of India and the people who are connected to them – become the main global players in the coming years and decades. The partnership has just started. Mah has entered the market. The Indo-French friendship will endure forever. And so will Mahuwa and the communities attached to it.

(This Substack is dedicated to Rahul Gajjar, who loved his drink as well as his innumerable French friends!)

If any one of you can access a well-distilled Mahudo, perhaps you can try making the cocktail (recipe below) concocted by one of the several mixologists and cocktail-makers working on this project. For more information, do visit, https://www.mahspirit.com/post/from-the-world-of-mahua.

Mah Highball

Inspired by tribal traditions that often combine Mahuwa with honey, this classic, simple and universal Highball family cocktail was created by Lucas from Symbiose, using products from Indian heritage.

Ingredients:

- 10 ml of well-concentrated tamarind water (or lemon juice)

- 30 ml of mead (if not available, a touch of honey)

- 30ml of Mah

- 30 ml of light beer or sparkling water

Recipe:

1. Fill the glass with ice cubes to refresh it

2. Pour the Mah, Mead and Tamarind water into a mixing glass filled with ice cubes

3. Mix everything vigorously with a spoon

4. Add the light beer

5. Mix gently

6. Pour into the cocktail glass, without the ice cubes

ENJOY!

What a spirited , heady tribute! Such a lovely narration. I hope all this wisdom garnered by the young scholars is documented and disseminated some day.We visited Tejgadh Academy in the early days as a Surabhi research team, so the story has context for me.

Oh Mah word !! 🥂