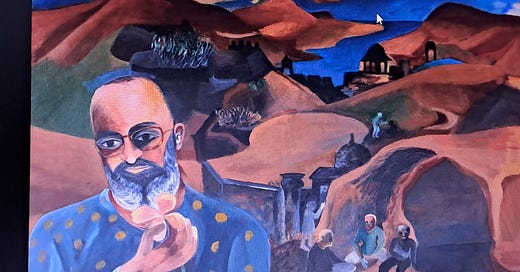

If artist Padma Shri Bhupen Khakhar was still amongst us, he would have turned 90 on this March 10. And how happy he would have been to know that just yesterday his 1996 oil on canvas painting, Champaner (officially called Untitled), was sold for Rs. 14+ crore at the Saffronart Spring Live Auction! The painting features his good friend, architect Karan Grover upfront on the right of the canvas, holding a champa flower, and celebrates the architect’s sustained efforts to get the medieval archeological site of Champaner-Pavagadh, 45 kms. from Baroda, World Heritage Site status by UNESCO.

Bhupen Khakhar, Untitled (Champaner), Oil on Canvas, 1996. Pic courtesy the Internet.

Since Bhupen passed away on August 8, 2003, our small town Baroda has never been the same. It is not as if there are no longer any good and great artists living in this city, but somehow Bhupen was different -- dramatic, with a sharp intelligence, a wry and witty sense of humour, empathetic, multi-talented, and equipped with survival skills typical of a person from a lower middle-class Gujarati baniya family from Khetwadi, Mumbai. He was a self-taught painter who developed his own unique style (but also a trained Chartered Accountant who was employed in Bharat Lindner, a small company managed by Savitaben Nanubhai Amin, who allowed him enough spare time to devote to painting as well as an assured monthly income until he became financially independent). He studied art criticism at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Baroda (in 1962, that’s when he moved to my small town from Mumbai) and became very close friends with artists Gulammohammad and Nilima Sheikh, Vivan Sundaram, Amit Ambalal, Jyoti Bhatt, P. Dhumal and others who lived here. He worked diligently on his painting skills and had his first exhibition in 1965. He sketched tirelessly, knowing that his drawing needed to be improved; his sketchbooks, if they are preserved carefully by whoever has them, would be very valuable indeed.

His first interest, though, was to become a writer. He wrote in Gujarati (Phoren Soap, Mojila Manilal, etc.) and most of his writing was translated into English by Naushil Mehta and Ganesh Devy. A few years back, while working on an exhibition project by the Sarjan Art Gallery in Baroda, I had contacted Ahmedabad-based artist Amit Ambalal. Amitbhai and Bhupen were thick as thieves. They got together often and loved to gossip to their heart’s content. When I spoke to Amitbhai about sharing some the priceless moments he had with Bhupen for the catalogue, he gifted me something even more invaluable – some letters that Bhupen had sent him. These letters (postcards and a couple of faxes) are extremely interesting and amusing because Bhupen writes about a completely imaginary immediate and extended family he has – a wife, Savita, four sons – Rohit, Kaushik, Dinesh (whose wife has left him because of his addiction to alcohol and gambling), and Rajni (who wants to open a toy shop in Alkapuri, Vadodara, to be financed by Amit!), some Ragi nani who has chickenpox and another Vimla who has to undergo bypass surgery at Hinduja Hospital, Mumbai. These characters hold forth over several letters, their persona carefully introduced and developed. In addition, friend Amit also gets a makeover – that of a philandering husband, willing to spend money over girlfriends, Ela and Navina, while wife Raksha (whom he is in the habit of caning every other day) and the two boys – Anand and Anuj – are in tattered and patched clothes. There are moments in these letters when actual persons such as Sunilkaka (Kothari, the dance critic and one of Bhupen’s oldest friends going back to their University of Bombay days) from Kolkata and Dr. Hegde (who was then away in Poland) also creep in. These letters illustrate how Bhupen’s fruitful mind could make up wild though entirely probable stories, weaving them in a wondrous web of complex familial events such as a wedding or a life-threatening illness, indicating towards his inherent writing skills which he worked upon but with not as much attention as his art-making.

Bhupen used his sharp sense of dramatic parody with the most telling effect. Once, he was invited to Haridwar by Gallery Espace along with Amit Ambalal, Anju and Atul Dodiya, to create a series of works that were later exhibited by the Gallery in a show titled, Leela. The Gallery had organized for its curator to interview the artists for the catalogue. Bhupen insisted that he will create his own interview – both the questions and the answers -- and the Gallery sportingly agreed. This interview was first printed in the catalogue for the Leela exhibition. Here’s the first question he framed himself and answered!

“When do you paint?

“If I want to do a good painting I have to start at 9 am. This is the time Lord Krishna has allotted to me. He is in my studio on the dot. If I am not there he disappears. Once I told him to keep the time at 10 a.m. He refused. He said that in the past he appeared before Meerabai at 6 a.m. She used to rise early while Narsinh Mehta was given 10 a.m. as he used to go to the Harijanwada at night to sing bhajans so he naturally got up late in the morning. My other complaint to Krishna is that he put on too much perfume like our minister Murli Manohar Joshi. Krishna ignored my complaint. He said when he was with Radha he never used perfume but Rukmini never let him go without applying perfume on his body.”

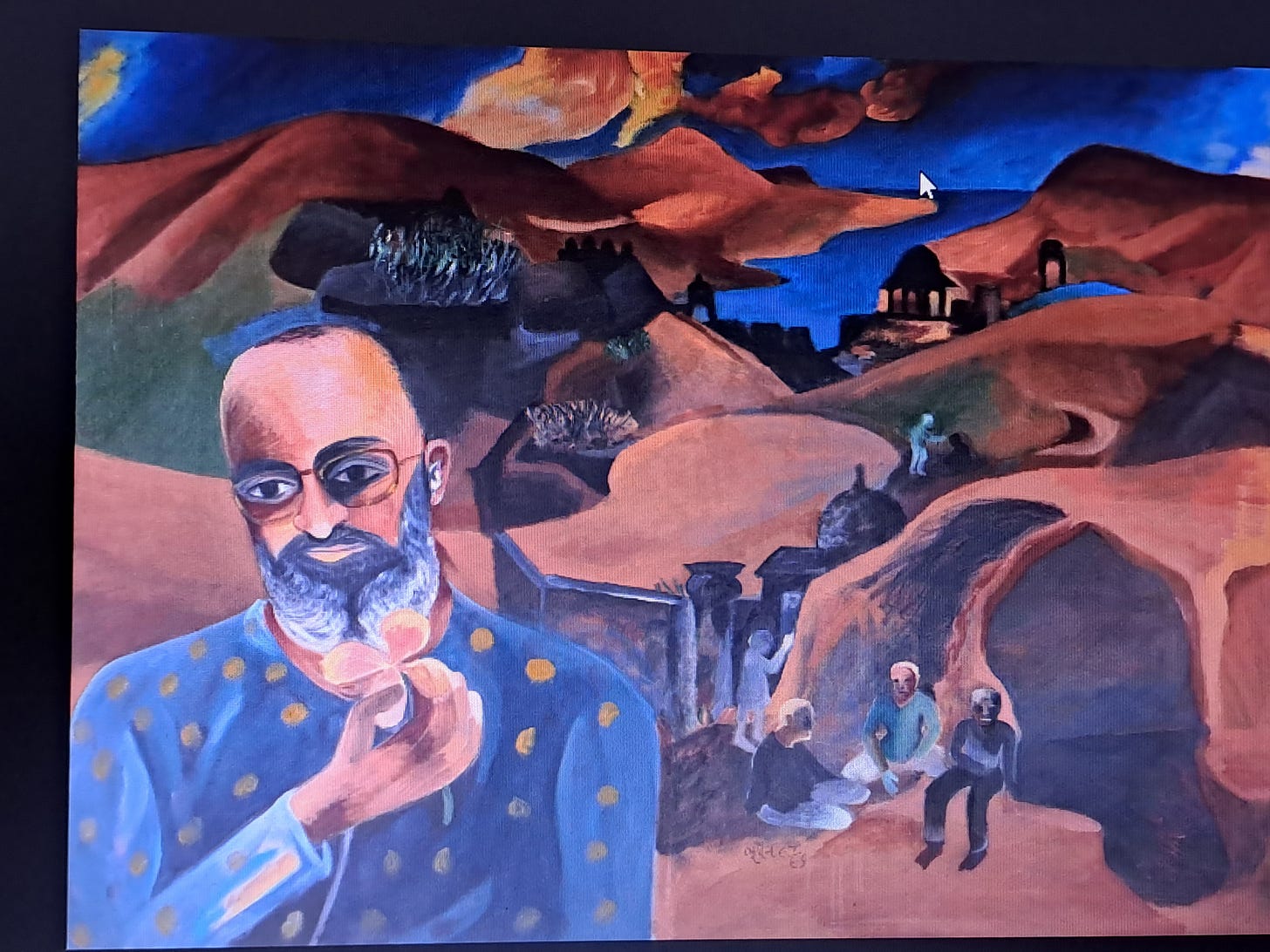

Man with a Bouquet of Plastic Flowers. Pic courtesy Contemporary Art in Baroda, Tulika, 1997.

Bhupen’s paintings came as a surprise, even in the kind of unusual, experimental, exciting work that was then (1965-80) being done at Baroda, whether at the Faculty or outside of it. He was tremendously interested in the life of very ordinary people and that became the subject of his artworks. Man with a Bouquet of Plastic Flowers (1975, collection of National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi) is one of his best-known works, and in his artist’s note to the question he asked, ‘Why plastic flowers?’, and he answered himself, tongue-firmly-in-cheek ‘Real flowers fade; a bouquet of plastic flowers is an eternal joy to the eye.’ That was a ‘middle-class’ insight which very few contemporary Indian artists would have dared to articulate in those days. In fact, talking of daring, the fact that he never had any formal training in art-making never deterred him from trying his hand out at painting in different mediums, printmaking and sculpture.

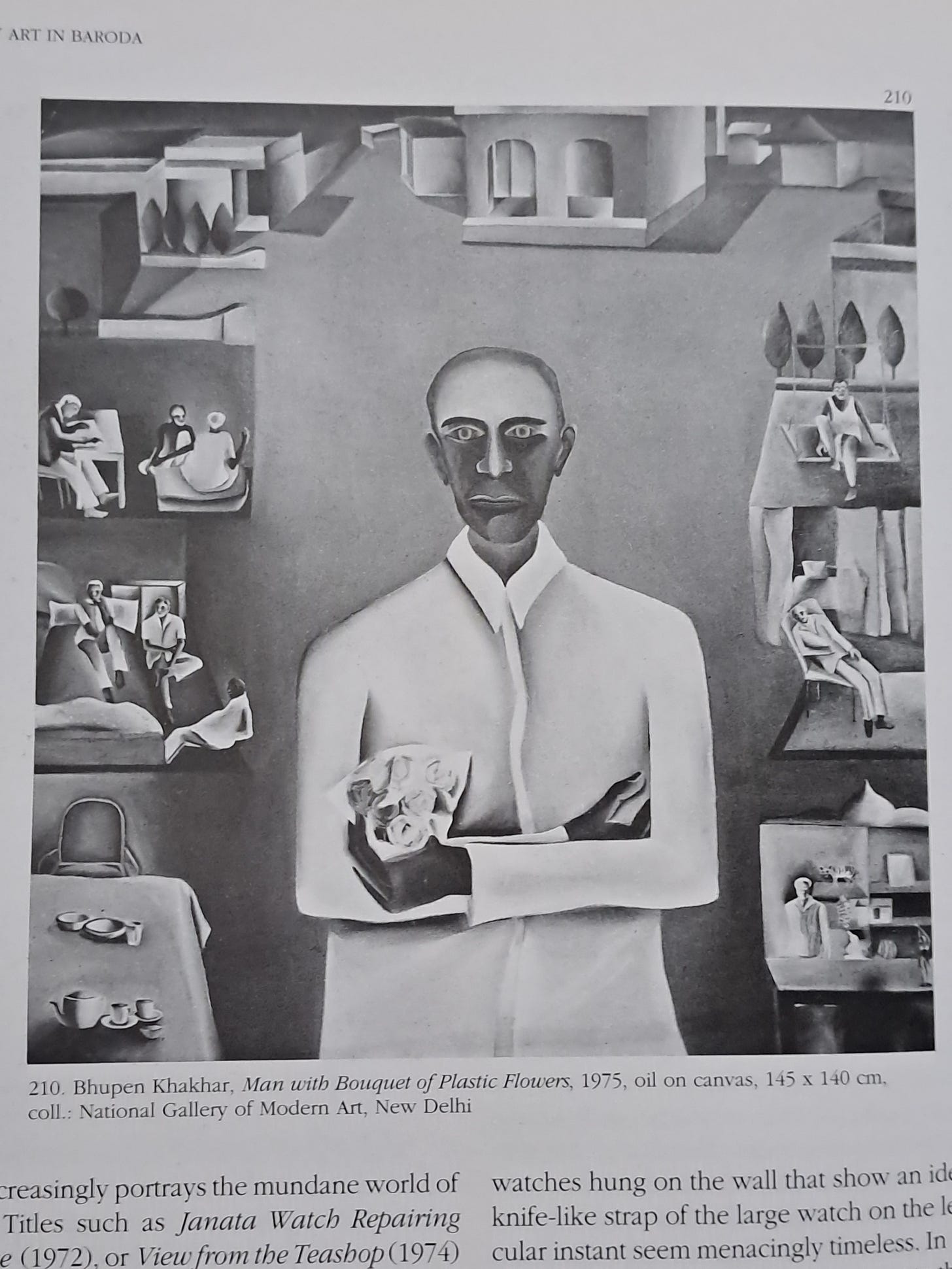

Vulcanizing. Pic courtesy Contemporary Art in Baroda, Tulika, 1997.

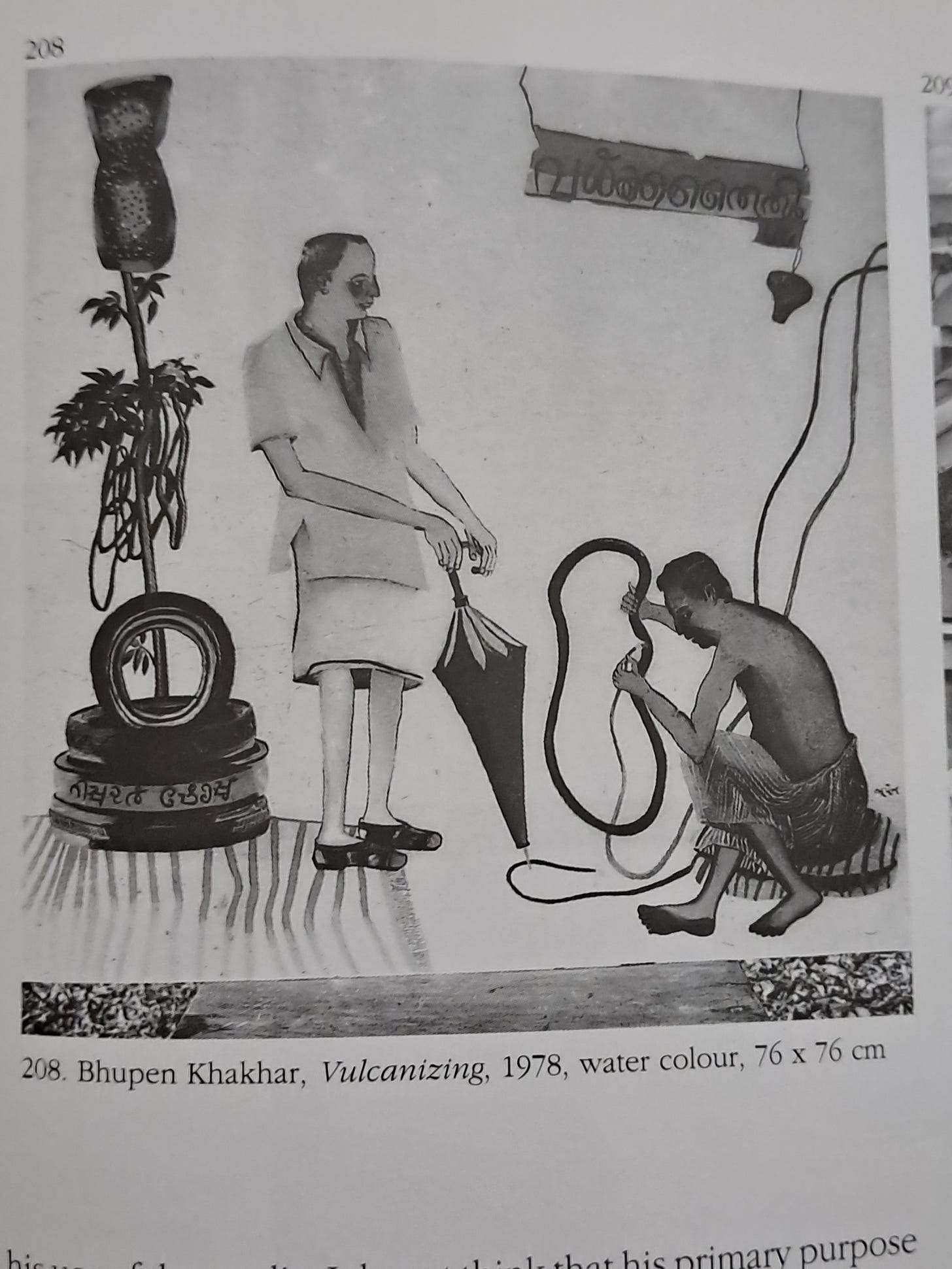

In continuation of ‘middle class’ dreams and aspirations, he conceptualized a solo show at the Chemould Gallery, Mumbai (1972) wherein he got artist Jyoti Bhatt to photograph him in various avataars (Mr. Universe, Made for Each Other, James Bond, and so on) that he put in the catalogue accompanying the show. Even though the ‘performance’ was really only for the photographer, documenting it as visuals and putting them in the catalogue was a way in which Bhupen shared the ‘performance’ with the viewers, and also extended what he wanted to express through it to his artworks in the gallery. This was the time when Bhupen was very much influenced by the Pop Art/Culture ideology and was essentially working on collages in which to express his sneering/celebrating of popular culture.

Dr Harsha Hegde, one of Bhupen’s closest friends explains that I wasn't surprised to find a motley group of poets, dancers, writers, economists, industrialists, doctors, shopkeepers, gardeners, philosophers, academicians and, of course, artists at his house. He used to celebrate the mundane and the ordinary clearly seen in his earlier works and his short stories. He would have conversations with barbers or tailors and he would make each one of them feel that he was one of them. Given his background he had a deep understanding and empathy for the ones who were somehow trying to eke out an existence and in his unique humorous way also exhibit their hopes and dreams. He was not prescriptive and deliberately void of any political overtones, a sensibility he continued to nurture all through his life. He used to teach arithmetic and mathematics to his Man Friday, Pandu's children and their friends (ranging from 5 to 18 years) while painting. Rewards for completing work on time would be food from a Chinese take-away or tickets for a film ... I am so happy that he is recognised the world over and had friends in all corners of the globe. That his bungalow, tucked in a leafy enclave of the small town of Baroda could be a magnet for individuals of all hues tells us that his choices of taking the path less traveled by has made all the difference not just to his life but a lot more to ours.

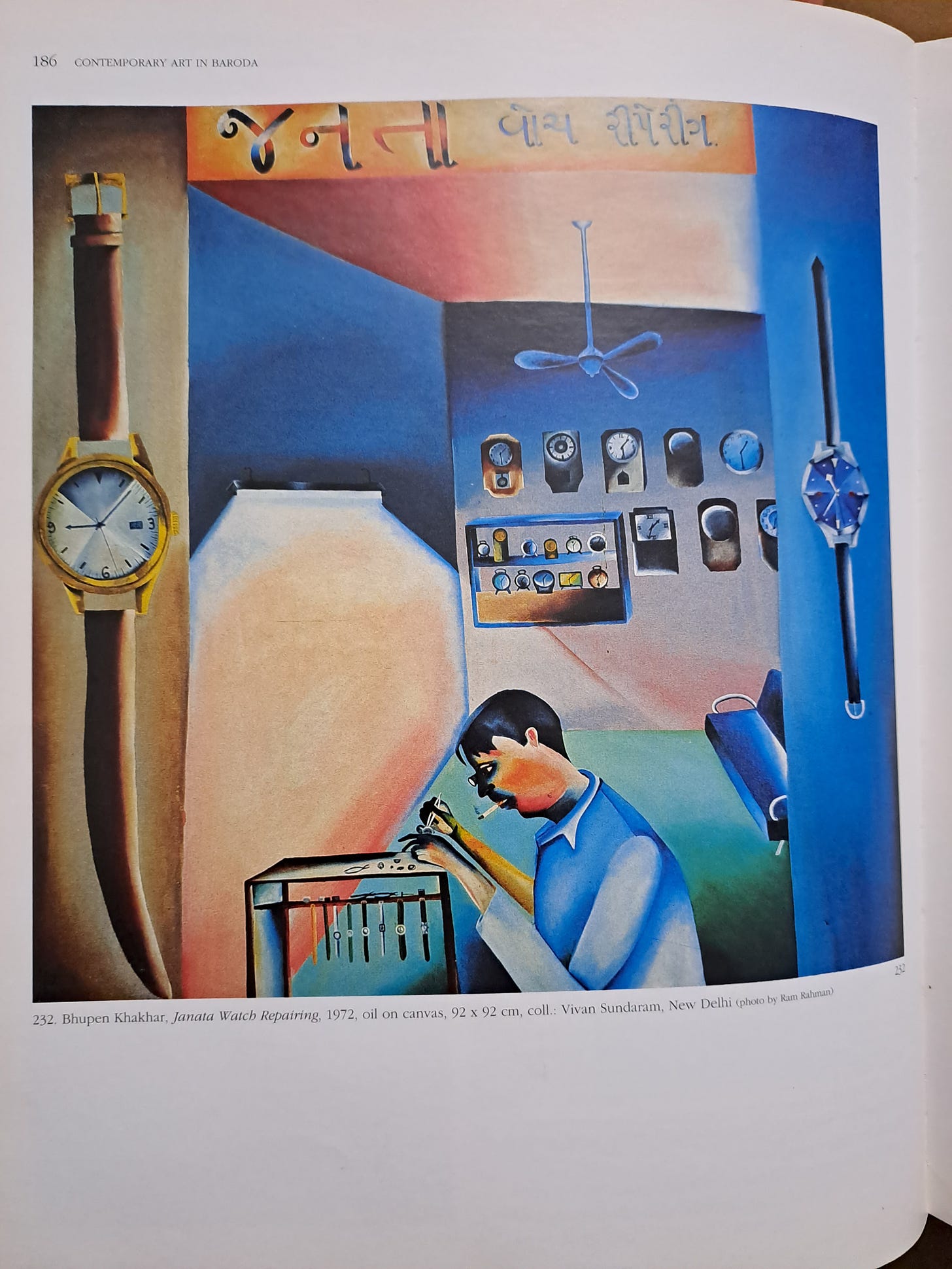

Janata Watch Repairing. Pic courtesy Contemporary Art in Baroda, Tulika, 1997.

After 1980, when his mother passed away, Bhupen stepped out of the closet and declared his homosexuality quietly through his works. It was one of the most significant moments in Indian contemporary art history. The most obvious one was, You can’t please all, a large oil on canvas that used the well-known allegorical tale of a man, his son and their donkey, watched by a naked man. As recounted by Brian Weinstein, one of the American collectors of his work, Bhupen explained the erotic element in his works to a “hushed class at the Faculty of Fine Arts of MS University, Baroda … He expanded this idea by saying that his portrayals of sexual intimacy, particularly between men, were not voyeuristic or pornographic because all the relationships expressed in his paintings and prints were based on love. He knew best because he was mainly portraying himself, his intimate experiences, and the lower middle class milieu of his origins in Bombay. Later he explained that the act of creating the erotic works and the paintings about disease that he suffered from released him from his inner passions and torments.”

Bhupen was one of the most important and significant artists whom many of us have had the good fortune to meet and interact with. His work, Celebration of Guru Jayanti (1980, whereabouts unknown) was selected to grace the cover of the seminal book Contemporary Art in Baroda (ed. G M Sheikh). He was honoured with the Kalidas Sammaan (Govt of Madhya Pradesh), the Padma Shri (Govt of India), the Prince Claus Award (Govt. of Netherlands) among many others. His works are in the collection of the British Museum, National portrait Gallery, and the Tate Gallery (London), the Museum of Modern Art (New York) and he was honoured with a vast Retrospective at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Spain, in 2002, a year before he died of cancer of the prostate in 2003.

There was an incident related to that last Retrospective, that I just can’t resist recounting. It is amusing when I think of it now but was nerve-wracking when I was actually dealing with it. In June 2002, when the Reina Sofia Museo in Spain organized this major exhibition of Bhupen Khakhar’s works, its curator wanted Bhupen to suggest a younger artist, an ideological inheritor of the older artist’s mantle, whose works could be displayed in a separate, smaller area but as part of the Khakhar show. Bhupen suggested Atul Dodiya and accordingly Dodiya’s works were exhibited at Espacio Uno. Given the significance of this show I sent in a detailed article to the Art India magazine that I write for. The then editor, rather unthinkingly and without informing me, reduced it to a small news item and, what’s more, used an image of Dodiya’s work to go with it. Bhupen flew into a rage, and cancelled his subscription to the magazine. When I met him, he subjected me to a furious litany of the “Bombay bias” of Art India. As luck would have it, the editor changed and I soon managed to get a detailed interview with Bhupen that Art India printed. That soothed the ruffled feathers and all was well!

Kiranji, don't bother about the subscription. I am glad you read and enjoy them!

Got to know about Bhupen sir through Harsha... but your research and insight, gives the man's life a whole new dimension.

Karan Grover's painting is a hugely ironic thing. I didn't even know of this piece.