The several decrepit brooms I saw chucked away at many crossroads on Diwali day in my small town made me think about this ordinary household product that we so easily take for granted. But what really triggered my interest was that later on in the day, when I was watching a Marathi tele-serial, where an elaborate Laxmi Puja was in progress, I suddenly spotted a brand new short-handled broom placed prominently among the various materials that were part of the Puja. Though I am also a Maharashtrian and have been present at any number of Laxmi Pujas at my aunt’s home in Mumbai, I had never seen a broom as part of the puja samagri. Where did this come from? What part of Maharashtra or in which specific community was this a part of their tradition? With so many Marathi families in my small town in Gujarat, I imagine some of them follow it as well. This was very interesting indeed!

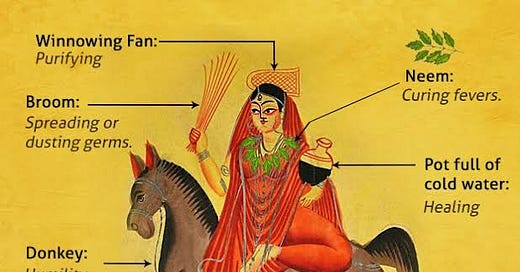

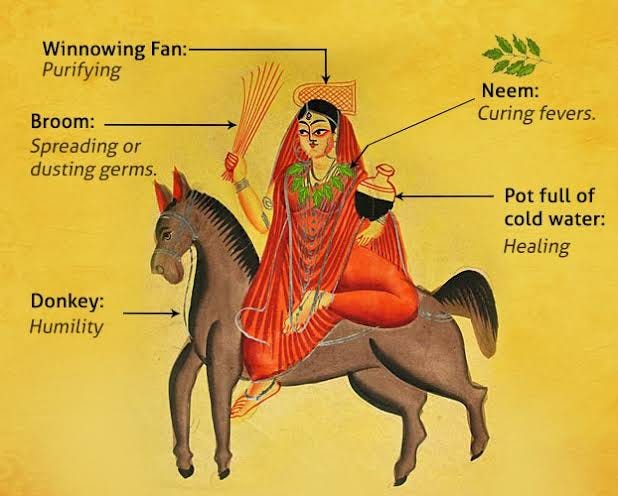

An Image of Goddess Sheetala Devi from folklore. Pic. from Internet.

The Internet threw up a lot of information, though unfortunately nothing about specific communities that actually worship the broom like I saw in the Laxmi Puja visuals in the tele-serial. I found, though, a lovely folk image of Goddess Sheetaladevi (worshipped to prevent attacks of smallpox that earlier took a lot of lives, as well as a gesture of thankfulness if the infected in your home survived). The goddess finds devotees in not just Hinduism, but also in Buddhism, folk and tribal cultures, and is featured holding an upright broom in her right hand. There is an ancient Sitladevi Temple at Mahim, Mumbai, in whose neighbourhood I spent almost all my vacations while at school. Made from some kind of black stone, it has an unusual shikhara and two short deep stambha flanking the entrance. I used to always be intrigued by a stout woman who was forever parked at the temple’s compound gate, with her decorated cow, trying to get you to buy a sheaf of green grass for a few rupees to feed to that cow. Sometimes there would be a wildly made up dark man with a large cloth sling bag and a broom of peacock feathers, waving it menacingly at passers-by. Most likely to be some kind of a tantric …

The Sitladevi Temple, Mahim, Mumbai. The cow continues to be a fixture. Pic from the Net.

Besides Sitladevi, however, several mainstream Hindu communities associate the broom with Goddess Laxmi. As a school-kid, it was my duty in our home to sweep the house and make the beds. My mother made sure that I finished the sweeping before the late evening lights in the house came on, for she believed that sweeping the house at eventide drives Goddess Laxmi out of the house. You also could not touch the broom with your foot or kick it around. If any elder saw you do it, you got a good whack (but not with the broom!)

The post-monsoon Diwali spring-cleaning drive that grips all homes to sweep out spider webs, dirt and dust from different nooks and crannies of the house to welcome Laxmi on Diwali and thus bring prosperity, has at its centre a good, strong broom (like a multi-tasking housewife-mother-professional), sometimes special ones with long handles to clean out-of-reach corners. On the night before Diwali, when the home is (hopefully) spic-n-span, the old broom takes its one last sweep around the home floors and the courtyard or porch and then the broom is discarded on the crossroad or if that is too far off then outside the compound of the house. This is one night on which the ‘sweeping out Laxmi after nightfall’ belief does not work at all!

Broom-making. Pic from the Net.

I suddenly remembered that Dr. Madan Meena, our Hon. Director at the Adivasi Academy at Tejgadh village, had once curated an exhibition section on Brooms for eminent folklorist and ethnomusicologist, Dr Komal Kothari’s Arna Jharna, The Thar Desert Museum (https://www.sahapedia.org/photo-essay-arna-jharna-the-desert-museum ). This Museum, about 20 kms from Jodhpur, another small town, was established in 2000 and is situated on 10 acres of land in Moklawas village. The website informs that this land was specifically chosen by Dr Kothari with great care -- it is surrounded by protected forest areas, sacred spots and waterbodies, and is a haven for desert flora and fauna. The air is filled with the sounds of birds and the watershed is regularly visited by deer and peacocks. Complexes of earth-red buildings in the local style of village architecture blend with the landscape.

Different kinds of brooms and their handles. Pic from the Net.

Arna Jharna exhibits a collection of the most ordinary and yet unconventional things, skills and art pieces that belong to various Rajasthani cultures. So while there is an extensive collection of musical instruments from every corner of Rajasthan, a specific interest of Dr. Kothari, there is also a large and diverse collection of pottery and brooms exhibited there that are produced from across Rajasthan. The actual products are backed with numerous videos that highlight the rituals and beliefs from which they originate as well as the poor and often marginalised communities whose labour and inherited skills keep the tradition alive. They also focus on the risks associated with musical instruments and broom production that would go a long way in sensitising visitors to the Museum. In fact, from time to time, the Museum holds broom-making workshops for visitors to introduce them to the craft of broom-making.

As perhaps the humblest object in the Indian home, palatial or poor, the ordinary broom has roots in the local ecology and traditional knowledge systems of the region. The Broom Project was supported by Ford Foundation, India, and directed by Rustom Bharucha, author of Rajasthan: An Oral History, and professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Bharucha was aided by Kothari’s son, Kuldeep, secretary, Rupayan Sansthan that manages the Museum. The display was designed and curated by the visual artist, Madan Meena.

Madan Meena has classified the brooms according to the different agrarian zones of Rajasthan identified by Kothari: millet (bajra), sorghum (jowar) and maize. Did you know that there are ‘female’ brooms and ‘male’ brooms? Well, the ‘female’ brooms are associated with Goddess Laxmi and are used to sweep the inside of the home, and always stored horizontally. The ‘male’ brooms are used in the courtyards, verandahs, porches, gardens and other outside areas. Obviously they are sturdier and capable of easily moving large clumps of dirt and small stones to one side from where they can be suitably disposed of. In Rajasthan, generally the ‘female’ brooms are called Buari and Havarni (Savarni in Gujarati), the ‘male’ being Bungra and Havarno.

More brooms! Pic from the Net.

Let me quickly describe some kinds of brooms on display at the Museum. The Jhoonjhli is made from jhoonjhli grass that grows in the Sirohi district. It is collected by the local Garasia and Bhil tribal communities and sold to broom-makers in nearby villages and towns. This is a tough broom and is used both in inner and outer spaces. The Khemep is an extremely versatile broom made from dry shrubs found on scrublands and sand dunes in Barmer district. In addition to being made into a broom that can be used inside the house as well as clean cattle sheds, the locals craft a strong rope used to tie around pots to draw water from wells and to make indhoni, the circular bed that women place on their heads to balance a pot of water. The Siniya broom is made from the small Siniya grass that grows in the arid Jodhpur area. It is sturdy enough to quickly clean cattle sheds. The Daab broom is more like a brush, and is made from the Daab grass that grows in the Jalore district and which is also used in several death rituals. As a short-handled broom, it is used to whitewash walls. On the other hand, Panni brooms are made by the sweeper community for use in cleaning public spaces and sweeping roads. They are made from grass that grows in Dausa district, and is a seasonal plant that grows in the soil loosened during the rainy season. All of us are familiar with the Guncho Khejur broom though we may not recognize it by this name. It is made by tribal communities from combed dried branches of the date palm tree and used for cleaning homes and built spaces of cobwebs!

Explains Madan Meena, “Largely the raw material for brooms comes from the north-eastern states and Rajasthan, and these include several wasteland species and seasonal grasses, harvest waste, fine twigs, hay, straw, plant leaves. These are bundled and piled onto trucks that reach the raw materials to almost every town and village across the country to the broom-makers.” Surprised? The requirement for brooms is so high that every settlement will have its own community of local broom-makers. In fact, in almost every district there will be a kind of broom that is known for some specialty. These brooms are identified by the raw material used as well as the way their handles are designed.

It is amazing that we often don’t know what is available in our own neighbourhoods!

What a story 👌

Loved your discoveries and the folklore!!