As somebody who has grown up in Sayaji Gunj, the Sayaji Baug or what it was then known as, the Kamati Baug, was extremely dear to us –as kids, adolescents and young people. Just a hop, skip and jump away from my home, that vast garden offered us so many options to explore and entertain ourselves – the Museum, the Zoo, the Band Stand, the Toy Train, Elephant/Pony/Bakra-gaadi rides, the Traffic Circle (where you could rent children’s cycles, tricycles, paddling cars and learn simple traffic rules to follow), to tumble about on the Junglegym, see-saws, swings …Then, as we grew older, it became the nearest and healthiest place to go for a brisk morning walk (not as crowded as it is today), and enjoy the wonderful seasonal flowers blooming in their beds that the gardeners were forever tending to.

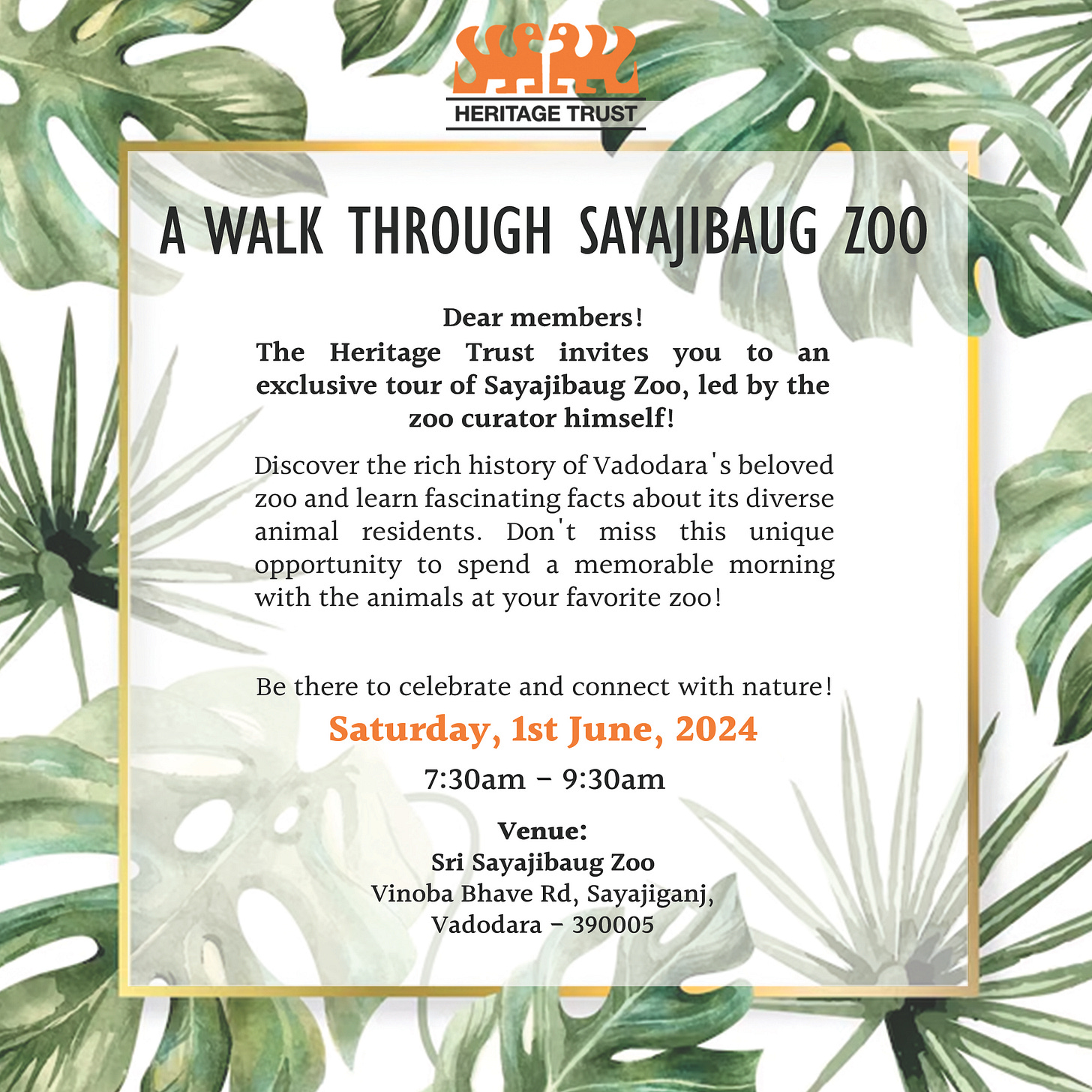

How we take the spaces we love for granted! Would you believe it … even today the Sayaji Baug is the largest public garden (112 acres) in the heart of a city in all of Gujarat. It celebrated its 145th Foundation Day on the 8th of this January. Surprised? This and much more interesting and inspiring information about our favourite public park was offered by zoologist Dr. Pratyush Patankar, who is currently the Curator of the Sayaji Baug Zoo and in-charge Director of the Sardar Patel Planetarium (1976) in the Sayaji Baug when he spoke about his Zoo at Heritage Trust’s quarterly Vaarsa ni Vaato (Conversations around Conservation) event at SEE Foundation in Makarpura GIDC on last Saturday. The Park continues to serve as much-needed green ‘lungs’ or continuously generating ecological capital that helps set-off the increasing pollution levels in Baroda on a daily basis.

The exotic birds at the Zoo are now housed in an open Aviary . Photo by Sriparna Seal

The Maharaja selected this land on the banks of the Vishwamitri river in 1875 that was then on the outskirts of the town, about 3 kms from the walled city, in a village called Kamatipura (it still exists, where the Kamdev Mahadev temples are situated on the Vishwamitri banks). Hence the garden was commonly and popularly referred to as Kamatibaug. The villagers of Kamatipura were relocated to Navi Dharti area. The land for the garden was specially selected by the Maharaja to create a more congenial relationship between the British Resident’s army that was stationed in Camp (Fatehgunj) and the local people who were not happy with the British decision to send the earlier ruler Malharrao into exile on apparently fake charges.

For the responsibility to landscape the ear-marked land into a public park with multi-faceted uses, the Maharaja appointed William Goldring, a British landscape architect, with a reputation for having worked on several different and prestigious garden landscape projects in England alone. He was invited to India, specifically to Baroda, to landscape the 700 acres then surrounding the proposed Laxmi Vilas Palace as well as the planned Public Park. In 1875, he was in charge of the Herbaceous Department at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, London. He was assisted by the young German horticulturist, Gustav Krumbiegel, then working at the Kew Gardens, London. The Maharaja also offered him employment as state horticulturist. Krumbiegel started his career in India in Baroda as Curator of the Botanical Gardens in 1893. He stayed in Baroda till 1908.

According to Dr. Patankar, while the Maharaja planned a Zoo in the Park as a part of an educational program for the people of Baroda, he also had a private zoo in the Palace campus. Interest in wildlife was a major passion with most royal families – while they enjoyed hunting as a sport (as against poaching which is a crime). For instance, the Maharaja had domesticated cheetahs, one of whom was named Alibaba, who were used to hunt blackbuck, the fastest antelope on the planet. Cheetahs are the only species amongst the Big Cats that can be trained; references related to cheetah-training are found in the Akbarnama as well, according to Dr. Patankar. There is a blackbuck sanctuary at Sunderpura, near Varnama village on the Vadodara-Mumbai highway, where there used to be a Shikaarkothi, where the Maharaja and his friends would enjoy a bout of hunting.

A sculpture of the Cheetahs and their Handlers at the Fatesinh Museum, L V Palace campus. Photo courtesy Smt. Manda Hingurao.

In the Fatesinh Museum on the Laxmi Vilas Palace campus, there is a lovely sculpture of two cheetahs on leash with their handlers. Patankar’s own parents who lived on Dandia Bazaar Road remember the handlers taking the blindfolded cheetahs for a walk down the road! Once the awareness of many species being endangered became globally widespread, the royal families were often the first to support, fund and become spokespersons for all wildlife-saving and protection initiatives. In recent times, Lt. Col. Maharaja Fatehsinh Gaekwad, Sayajirao’s great grandson, was the Chairperson of the World Wildlife Fund for India. Sadly, cheetahs went extinct in India a year after Independence.

The idea of the Zoo is a European concept, explained Dr. Patankar. The whole of Europe was a conglomeration of different royal houses. When the world opened up towards the end of the Middle Ages, and ships sailed across the world discovering new continents, unknown countries, strange-looking animals and birds. This led to a flourishing trade in exotic species as well as spices! People were excited to see and observe animals and birds from a safe distance exhibited in enclosures called ‘Zoo’, that they could never see in their own forests. The idea caught on with Indian royalty too. Those states which were financially well off managed to establish large and well-maintained Zoos – these included Baroda, Mysore, Junagadh, Gwalior, Hyderabad, Udaipur, Kolhapur …

The privacy of animals and safety of their keepers was very important in Zoo planning in earlier times. Feeding of animals was never compromised. They were given the right food, enough of it and on time. Animals reproduced well in captivity, always a sign of a good Zoo. Also breeding was done systematically and scientifically so that the bloodlines were maintained. So in earlier times too, unknowingly nevertheless, Zoos were well managed.

In Sayaji Baug, the Zoo was designed smartly. The herbivores and carnivores were separated, mostly each on either side of the Vishwamitri river that flowed through the Park. Dr. Patankar maintains that the Waghkhana (tiger enclosure) with the open space behind the cages is one of the best designed enclosures he has seen with use of very strong material that made sure both animal and viewer were protected. We can’t make that kind of building any more. So we have kept all of the old structures intact and repurposed them for other functions required in the Zoo.

The new Aviary design allows for free movement of the birds as visitors quietly move along the walkways. Photo by Sriparna Seal.

While on the Waghkhana, I must share an unforgettable event. When I was in high school, one afternoon, a student from the Science faculty wandered into the Zoo and reached the open enclosure in the Waghkhana. A tigress (I forget her name now but I used to know it) was resting in the shade of a bunch of bamboos. God alone knows what got into the young man’s head, he jumped the broad mehndi hedge, climbed the 20+ foot high metal bars, jumped into the enclosure, and walked to the tigress, who was now awake and sitting up and probably puzzled as hell. The idiot then, as the rumour went, slapped the tigress. In a fraction of a second, the surprised tigress whacked him so hard across the head, it broke his neck and he slumped, dead. The tigress’ claws almost wiped out a side of the student’s face and it had begun to bleed profusely. It was believed that the tigress had probably tasted human blood so for a number of years, the poor animal for no fault was kept in isolation and the keepers were very careful during feeding time.

After this incident, the one single reason that all of us, then kids, had to go to the Waghkhana was to peer at this tigress alone in her cage. On one such winter morning, a bunch of us were in front of the Waghkhana (which now housed a few lions and lionesses as well), and an empty bullock cart rattled down from the main road (at that time there was a regular thoroughfare that allowed vehicular traffic from Karelibaug to cut across the Park, cross the bridge and exit the second gate opening on the Fatehgunj main road near the Fine Arts Faculty). As the big cats in their cages smelt and saw the bullock, they all got up, sauntered towards the front of their cages, their faces up against the bars, eyes fixed on the bullock, some of them emitting a low, hungry growl. The bullock sensed the danger and began to nervously paw and kick the ground, wanting to get out from that space in the fastest possible time. The empty cart shook and trembled. The cart-driver who was quite relaxed till then, with no deliveries to make and an innocent desire to look at the lions on his way to work, sprang to his feet, pulling at the ropes to control the terrified bullock and his shaking cart. As we crouched in a corner, hoping the bullock wouldn’t rush in our direction, we saw the cart driver finally able to turn the bullock’s head away from the lions, and drive the cart away.

I have never seen a heavy bullock cart scampering away so fast in my entire life!

(to be continued …)

l

Go to this link to register : https://forms.gle/GjbQ8S2jciPSkCdQA