In the late 1990s, there was a student-couple, Hema Hirani and Chintan Upadhyay, studying painting at the Faculty of Fine Arts. Quite talented, they went from strength to strength, their graduate display artworks catching a lot of attention and as they left my small town, seeking their fortune in Mumbai and Delhi, success followed them slowly and steadily. They were smart and quick learners and so even though both came from small towns themselves, they managed to weave their way deftly through the quicksand world of art galleries in metro cities, cultivating a market for themselves, until they could live on their own terms. During the short art boom time in India when artists became celebrities and were pursued by the paparazzi, these two led the bandwagon, their appearances at cultural events marked by in-your-face glamour! And that too, in the pre-Android phone days when all you could aspire for was a pic on Page 3 of the printed newspaper with much difficulty, and not the ease with which you can be splashed all over social media.

Sometimes though good things don’t last as much as we hope and expect them too. The relationship hit a rocky spot and never recovered, going from bad to worse leading to a messy break up, and a short while later to the gruesome and shocking murder of Hema in 2015. Though most of the actual murderers were nabbed, except the main person to whom either Hema owed money or who owed money to Hema, the police also arrested Chintan on suspicion that he could have played a role in the murder. He was refused bail and sentenced to a life in jail by the Bombay High Court. The family appealed against the judgement and the Supreme Court granted him bail in 2021. The main accused, one Vidyadhar Rajbhar, whom both the artists knew well, is still absconding.

The Partapur landscape.

Keeping aside the personal, in terms of artistic engagement both artists were seriously engaged in raising social issues via their artistic output. So, it was no wonder that in 2003, Chintan Upadhyay established an experimental project, the Sandarbh Art Residency, at his native birth village (it is now a midsize town), Partapur, in Banswara district, southern Rajasthan on the border with Gujarat. He was supported by his cousins, Lochan and Yatin. The Upadhyays are a large, well-known and forward-looking family in Partapur with extensive agricultural land, an English-medium co-ed school run by one of the daughters-in-law, and an NGO that is involved in developmental work in nearby villages. During the COVID years, with the help of a family friend they established a small soap-making unit offering employment to locals, especially women, that has now blossomed into a large unit manufacturing various cosmetics for a well-known brand.

The Sandarbh Residency was originally designed to invite urban, formally trained artists from art schools to live in a village environment and understand how the locals look at the practice of art, how they create ‘art’ themselves, and how they react to what is created by ‘urban’ artists. Would both these groups come together to create something artistic and meaningful, sustainable and glocal (global+local) in nature, was the question posed at Sandarbh.

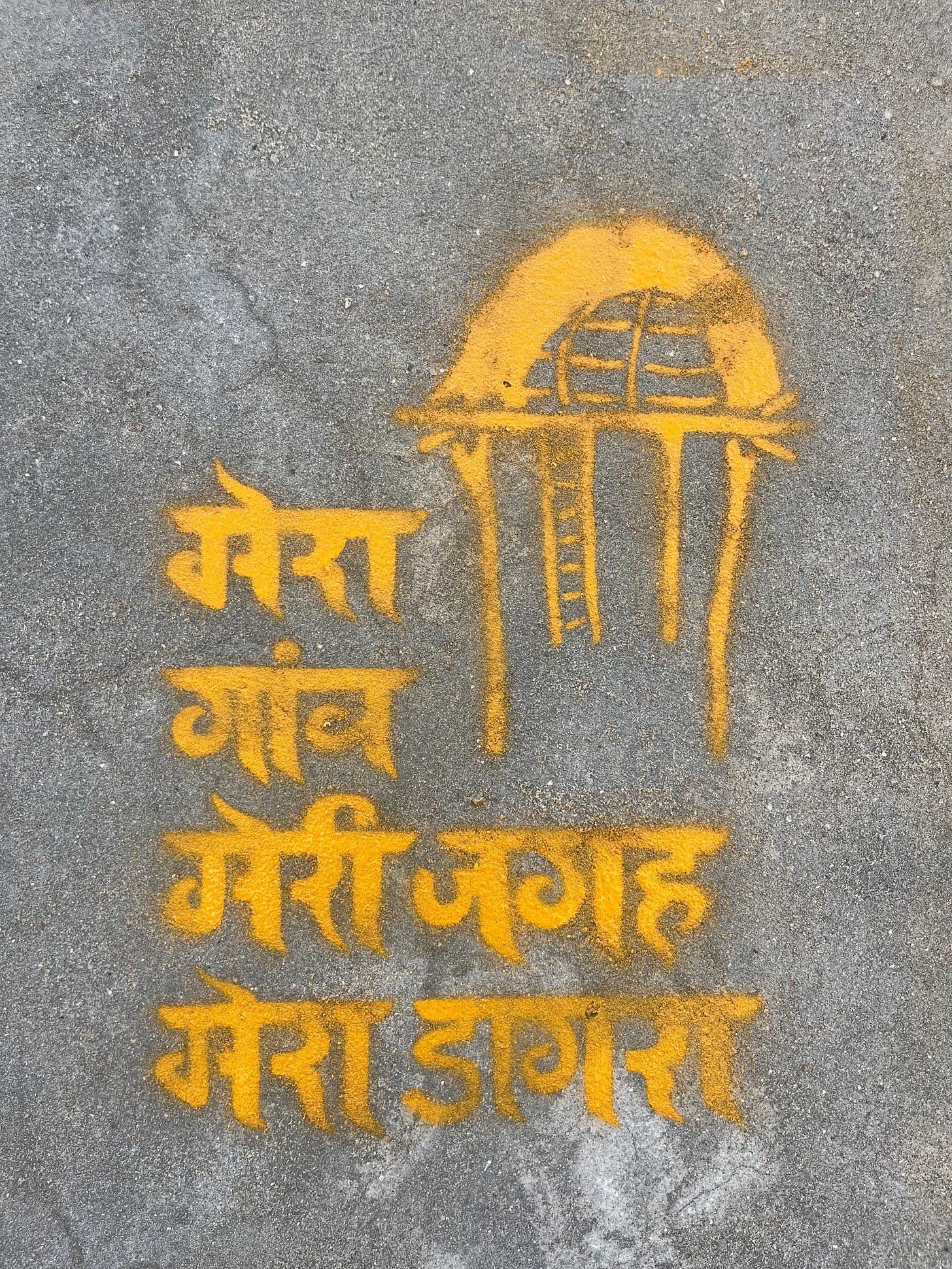

A Stencilled work by Eva Joy Lawrence. It was painted across common walls in Partapur. Photo by Sandarbhart.

A continuously evolving project, the Sandarbh Art Residency is held almost every year, when for about 2 weeks in the winter months, it hosts artists from across India and abroad, who interact and work with local artisans, craftspeople, folk artists, and curious young people to produce artworks that meaningfully relate to their experience in Partapur and adds to their own artistic development. The Partapur experience was so appreciated that soon after it was started, Sandarbh even collaborated with artists in the UK, Europe and USA to replicate the same experience with residencies in rural areas in these countries. More than 300 artists from all over India and from 15 countries have participated in Sandarbh since it was established.

While on a walk around the village, Lochan pointed out to me an old, unused vegetable market that they had cleaned up and converted into a stop-gap gallery to install artworks during one Residency when there were such a large number of artists who created so many works that they needed this large vegetable market with readymade concrete platforms for the display, such that all of Partapur and nearby villages came to see, enjoy and participate!

Anthony Shepherd, Milk and Human Kindness, installation. It includes images and actual materials used in cattle herding and the processes locally followed in cattle management in individual homes — the stainless steel milking pail, a large vat for mixing cattle feed, a drying leaf of a palm that the buffaloes love, a branding iron to establish ownership, a couple of T-shirts for the cow herds (the contemporary twist!), and the design of a logo for the family that sells the dairy produce, that focusses on the product being eco-friendly. Photo by Sandarbhart.

The unfortunate incarceration of Chintan followed by the COVID years put a temporary brake to the activities at Partapur. But over the last few years, Chintan’s cousin brother, Baroda-based Lochan (also a trained artist from the Baroda Fine Arts Faculty) and his art historian partner, Shilpa Rangnekar, have been spearheading Sandarbh, quietly and steadfastly. Last year, my friends and associates, Zahir and Ruchita, running Artcore in Derby, central UK, decided to work with Sandarbh for their annual Residency programme that includes getting two British artists to India along with a couple of artists from India. And so Equilibrium happened, supported by Arts Council UK, via Artcore.

Since a long while, Shilpa has been working on the idea of Equilibrium that succinctly captures the essence of the work they do with the guest-artists at Sandarbh. Every year, the word takes on new meanings or adds to its existing meaning, delightfully taking the idea forward every year. This year’s 4-week Residency (January 25 to February 25, 2025), included sessions of talks, presentations and workshops with women’s self-help groups in and around Partapur and through the ensuing dialogues, inform the final artworks they would produce at the end of the Residency, conducting a creative skill-enhancing workshop at a local school, and, if possible, Sandarbh would support artists in developing projects, along with the women members who have potential for a collaborative practice to emerge.

Dipal Sisodia is an alumnus of the Fine Arts Faculty, Baroda, who participated in the Residency in 2123. At that time she had worked with Kachribehen, a woman from Semalia village, who used to make dolls for herself as a young girl. Over a series of interactions, Dipal re-ignited that interest and as Dipal was also interning with Sandarbh 2025, the work of Kachribehen made over the last two years was also exhibited. Photo by Sandarbhart.

So the two British artists who made it to the Residency were Eva Joy Lawrence and Anthony J. Shepherd and the Indian artists were Aditi Anerao and Deparna Saha. All of them were completely involved in the several tasks planned for them by Shilpa who had meticulously organized the meetings, their travel to nearby villages as well as historical places of interest, access to raw materials, and looked after their stay and meals. While all four artists created numerous artworks, I will highlight the most interesting ones they created, especially those that involved them taking help of others while the primary idea was theirs.

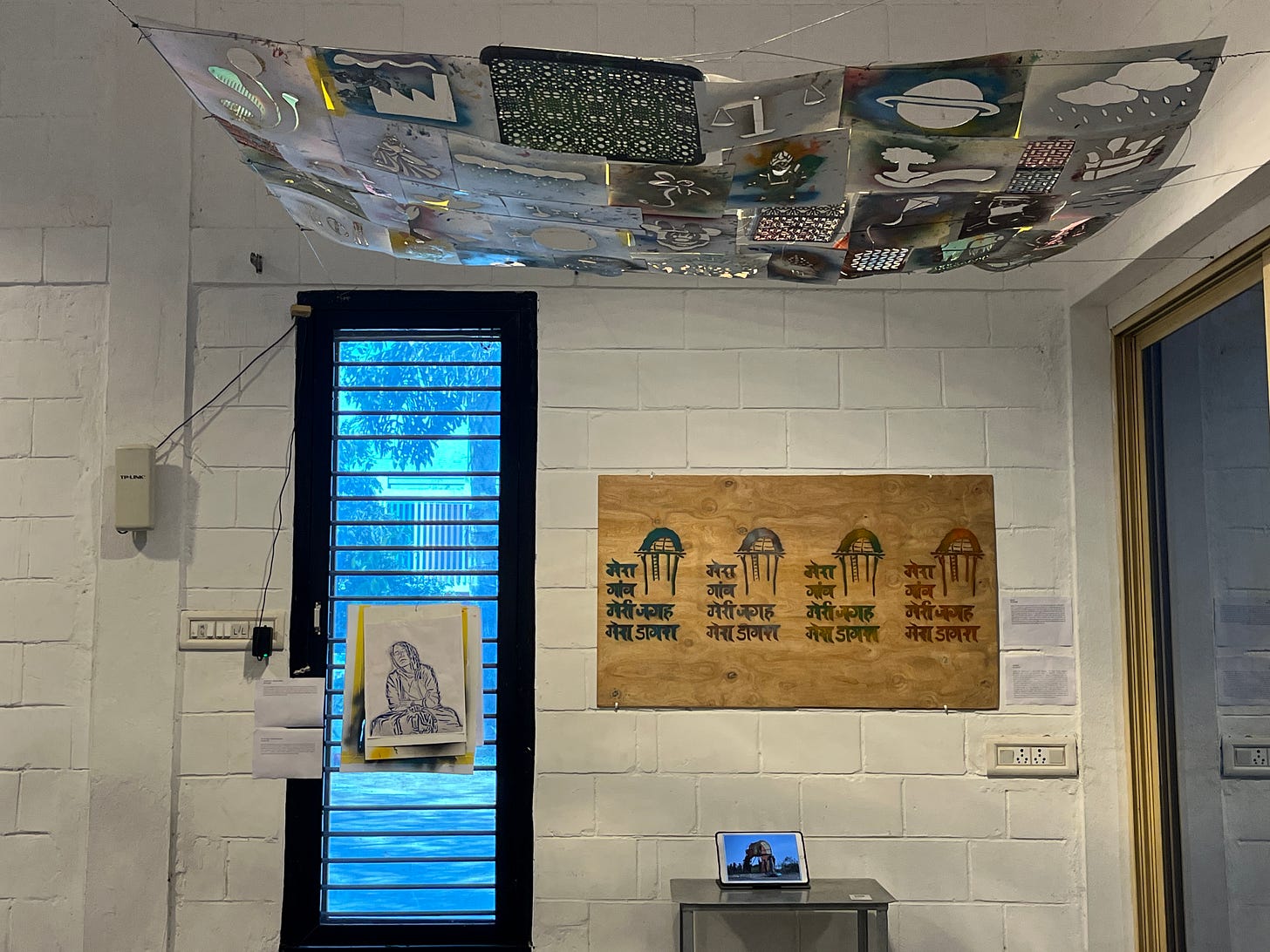

Mera Dagra, Collaborative Installation by Eva Joy Lawrence, Snehal Pradhan, Aditi Anerao and Anthony Shepherd, Photo by Sandarbhart.

This year’s Equilibrium was marked by a visually striking collaborative installation, made by the participating artists supported by women of the nearby Bargoat Mohalla village. The installation called Mera Dagra imitated a machan-like structure built by farmers in fields with standing crop, allowing them to sit/sleep in it especially during nights to shoo off marauding animals and birds. But this Mera Dagra, was different – with a canopy made of colourful cloth, it became a sturdy and special space created by women for women, a judgement-free space, only their own – a third space, so to say, separate from a work space and a home space! On the other hand, Anthony was so impressed with the local, natural, animal-friendly way of milking cattle, as against the mechanized, non-personal manner followed in his own country that it inspired his work, Milk and Human Kindness!

Eva Joy Lawrence turned this corner, even using the ceiling, to stretch her use of stencils in creating art! Photo by Sandarbhart.

Aditi Anerao, a trained architect and product designer, was taken up by the array of contemporary jali patterns she found on a largish area in Partapur where the Bohra community has its homes – enough for her to bring out a handy little booklet, Patterns in Partapur! She also worked with a talented young local potter, Ravi Prajapati, to create a collection of clay lamp shades.

A very interesting experiment in product design! Creating a terracotta lamp by Aditi Anerao and Ravi Prajapati, local potter. Photo by Ruchita Shaikh, Artcore.

While Eva Joy worked on the Mera Dagra installation, converting the stenciled slogan of My Ram, My Village, My Ayodhya that she found extensively painted on the walls of village Madkola, into that of a more inclusive message -- My Village, My Space, My Dagra -- she found an interesting accomplice in the format of the stencil as an instrument of art-making. Makeshift stencils were happily ‘discovered’ in common household items – all manner of sieves and strainers found abundantly in any Indian kitchen! It became the main factor used by the artists and school students to create a fascinating and colourful mural on one of the school walls.

Deparna Saha mapped the wall with the villages she visited to pick up her Flowers of Vagad!. The printed books were displayed on the table in front.

Deparna Saha created Flowers of Vagad (the Partapur area is also known as Vagad Pradesh), a modest pictorial publication that highlighted women from the neighbouring villages, their never-say-die stories of resilience and the foods that they loved to eat and those that they cooked for their families. In all these endeavours, talented young boys and girls helped and supported the artists, learning by watching and doing, in the process. All that these young boys of Partapur want to do is migrate to Ahmedabad and Baroda and open tea stalls there, says Chintan to me. Surprised, I laugh and turn around to look at him to see if he is joking. He is not. I want them to know that there is life beyond just earning money and survival, he continues.

Yes, that is what Sandarbh is all about. As is Equilibrium, in so many more ways than one.

An installation by Anthony Shepherd. I find an interesting ‘Sandarbh’ here and I would like to quote Deparna Saha from her project Flowers of Vagad, ‘Like wild flowers growing in unexpected places, their individuality often goes unnoticed, yet each one adds colour, resilience and beauty to the landscape of Vagad’ ! Photo by Sandarbhart.

.

Your writings introduce a fresh genre in writing....Writing about Human stories( Hema & Chintan) objectively sans judgement. Very touching. Art initiatives to integrate Rural/Urban & Global art fraternity is wonderful. In my sunset years, these writings provide a great solace. Than you Sandhya ben.

Liked the caption to the story!